You are currently browsing the daily archive for December 11, 2011.

Chapter Seventeen – Unsustainable

In chapter sixteen Deutsch goes after The Red Queen, though he never mentioned the book by name. In chapter seventeen, the attack is much more deliberate. I’d enjoyed Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel, feeling that it was a good explanation of why Western civilization developed so much faster than the rest of the world. But Deutsch takes a much different view.

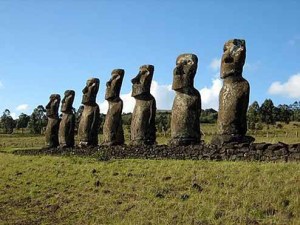

That gets ahead of things, though. Deutsch begins by returning to the Spaceship Earth misconception he discussed in chapter three, this time with the example of Easter Island. This story of people wasting their resources is shown to be not an example of how careful we must be with our resources, but instead a case of how failing to solve problems inevitably leads to disaster. The Easter Islanders were not like us, because they did not, and could not, solve the problem of a shrinking forest. Instead, they just kept following the dictates of their static society, cutting down trees and building statues, until all the trees were gone. Why, Deutsch asks, didn’t they travel to other islands and acquire seeds to plant a new forest? Why didn’t they trade with other cultures? Why didn’t they simply leave their small island home? Because, Deutsch answers, they did not know how.

The Easter Island statues. Why did the islanders keep building statues? Why didn't they instead solve their problems? Because they did not know how.

This leads to a discussion of sustainable versus unsustainable societies, and the double meaning of the word “sustainable.” Sustainable societies remain the same. Our society is unsustainable. We have lots of problems, some of them dire. If we don’t solve these problems, we will not survive. But this is the definition of a dynamic, versus a static, society. “You have to live the solution, and set about solving the new problems that this creates.” (p 375)

And then to Diamond and his book. Deutsch begins the assault with the following claim:

“The conditions for a beginning of infinity exist in almost every human habitation on Earth.” (p 378)

This is essentially the antithesis of Diamond’s claim that modern civilization arose in the West because of the abundance of natural resources there, and the paucity of such resources elsewhere. Deutsch basically claims that Diamond is telling “just so” stories about the world, stories that seem plausible, yet if conditions were different a different story could equally be plausibly told. The Americas were home to no domesticable animals with the exception of llamas. Diamond tells why llamas were not suitable for domestication beyond their native Andes mountains. But if someone had thought to do it, Deutsch contends, then Diamond could equally have told the tale of how no other civilization arose to combat the colonizing Americans because all other societies lacked llamas. Similarly, if the Polynesians hadn’t figured out how to navigate the Pacific, we’d talk of the Pacific as an impenetrable barrier to human colonization.

Deutsch’s point is that we cannot know what we have not yet discovered. Diamond’s point is that it was a lot easier for Asians and Europeans to discover things like animal domestication and agriculture due to their friendlier environment. I hate to equivocate for a second chapter in a row, but I believe there is still truth to be found in both stories. I don’t think one can completely discount geography, climate, and so on in telling the story of just how and why the Enlightenment happened when and where it did, any more than one can discount conditions on Earth that led to the evolution of complex life. It’s not all pulling yourself up by the bootstraps. In some times and places, the beginning of infinity was simply more likely. The rough terrain and isolated islands of the Greek world made the flourishing of the Ionian scientists more likely. It didn’t make their brief flowering a sure thing, but certainly there are extenuating reasons why it happened there and not, say, in the middle of Turkey.

In the same way, I believe I am the person I am because of choices I’ve made in my life. But there is no denying the fact that if I had been born in Afghanistan to a Taliban family, my available choices would have been different, and I’d likely be a different person than I am today, sitting in a cozy house far away from privation and violence. Such thoughts don’t invalidate who I am, but they do help to put my life in context.

Regardless of why it happened, though, I think the important thing to celebrate is that it did happen in the West, and that Western culture and values really did play a crucial role in the beginning of infinity, in the same way that having two free hands helped the first members of our genus to begin to use technology to alter their world.

But I think Deutsch is right to insist that once ideas became the dominant force in history, it is a mistake to look for mechanical explanations of it. “Why, for instance, did the societies in North America and Western Europe, rather than Asia and Eastern Europe, win the Cold War? Analysing climate, minerals, flora, fauna and diseases can teach us nothing about that. The explanation is that the Soviet system lost because its ideology wasn’t true, and all the biogeography in the world cannot explain what was false about it.” (p 381)

and

“(M)echanical interpretations of human affairs not only lack explanatory power, they are morally wrong as well, for in effect they deny the humanity of the participants, casting them and their ideas merely as side effects of the landscape.” (p 381)

Again I find myself agreeing with Deutsch because of the strength of his argument. Progress really is all about ideas. All people really are universal explainers and so are capable of beginning infinity in any environment. Yet I do still find myself agreeing with Diamond. Some environments are more conducive than others to the birth of our modern society. Was our latest beginning of infinity, The Enlightenment, begun in a highly conducive environment, or was it just an extremely unlikely fluke that might have easily (or more easily) started elsewhere? I don’t know, but couldn’t it be that some tradition, from ancient Greece and the Renaissance, still was in the air in Europe, and helped nudge things along? Couldn’t it be that ample food, lessened violence, and (I believe a big one) the failure of various religious traditions to get along with one another have made our beginning of infinity at least a little more likely at that time and that place?

But there’s so much more to this chapter than just the disagreement with Diamond – so much more! Paul Ehrlich is in for some harsh criticism, this time well-deserved when looked at through my new Deutsch-colored glasses. Just like Malthus, Ehrlich makes predictions about the future that are in fact pure prophesy (see the review of chapter nine). We cannot know what we have not yet discovered. We can’t know what solutions will come about due to creative thought. Without these solutions, certainly we are as doomed as Ehrlich predicted in the 1970s. But it has always been so, and always will be so as long as we live in a dynamic society.

And this is the great mistake I’ve been making, essentially all my life. I’ve been on the wrong side of “the contrast between two different conceptions of what people are.” (p 387)

Deutsch describes those two different conceptions, in a description of why color (or colour, in British English) television is not, in fact, the harbinger of our doom:

“In the pessimistic conception, (people) are wasters: they take precious resources and madly convert them into useless coloured pictures. This is true of static societies: those statues (on Easter Island) really were what my colleague thought colour televisions are – which is why comparing our society with the ‘old culture’ of Easter Island is exactly wrong. In the optimistic conception – the one that was unforeseeably vindicated by events – people are problem-solvers: creators of the unsustainable solution and hence also of the next problem. In the pessimistic conception, that distinctive ability of people is a disease for which sustainability is the cure. In the optimistic one, sustainability is the disease and people are the cure.” (pp 387-388)

And there it is. My mistake. I believed that people are the problem. This is of course ridiculous. The history of life on Earth is nothing but one disaster after another. The dinosaurs were wiped out, not because an asteroid hit the Earth, but because the dinosaurs didn’t know how to avoid the collision. Every species lives in a nasty place on the brink of extinction, which is why they all eventually do go extinct. Only humans have the potential to see the situation they’re in and take control of it. We’re not the problem. We’re the solution! Oh, how wrong I have been!

Problems are inevitable.

Problems are soluble.

All triumphs are temporary.

All evil is due to a lack of knowledge.

Only progress is sustainable.

The Principle of Optimism, spelled out in these five phrases, must become (and has become) the way I see the world. Starting now.

Now let’s turn this new-found wisdom on the climate change and carbon dioxide emission problem of today. Deutsch is no global warming denier. He says, “Regardless of how accurate the prevailing climate models are, it is uncontroversial from the laws of physics, without any need for supercomputers or sophisticated modelling, that such emissions must, eventually, increase the temperature, which must, eventually, be harmful.” (p 390)

But then Deutsch turns the Principle of Optimism on the very real problem of global climate change. The solution to climate change cannot be to retreat to a “sustainable” lifestyle. For that would leave us incapable of dealing with the next problem, the one we don’t even know about yet, just as in 1900 or 1970 we didn’t know about the pending greenhouse gas crisis. Instead, we have to solve every problem with ideas – and note that these ideas inevitably will lead to more problems. Problems are inevitable. Problems are soluble.

And, to keep in mind the real dangers, “No precautions can avoid problems that we do not yet foresee.” (p 393)

So the solution to the climate change problem must be new ideas, better ideas, to help us take better control of our environment. We do not live on Spaceship Earth. In order to survive, and thrive, we must create and control our own life-support system.

“Some such plans exist – for instance to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere by a variety of methods; and to generate clouds over the oceans to reflect sunlight; and to encourage aquatic organisms to absorb more carbon dioxide. But at the moment these are very minor research efforts. Neither supercomputers nor international treaties nor vast sums are devoted to them. They are not central to the human effort to face this problem, or problems like it.” (p 394)

Nuclear fusion as it might happen on Earth. Why don't we have such reactors on Earth? Because we do not yet know how.

Oh, how wrong I’ve been! Sustainability is not the solution, it is the problem. People, with their unique ability to create new knowledge through good explanations, are the solution! We are our best, and only, hope.

There is but one chapter to go. As we near the end of this remarkable book, we find ourselves once again at . . .