You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘meaning’ category.

I wrote a while ago about Darmok, one of my favorite Star Trek episodes (second only, I think, to the finale, “All Good Things”, though “The Inner Light” and “I, Borg” are awfully close). I’m writing about Darmok again for two reasons. One, in this week’s Cosmos Neil de Grasse Tyson told the story of Gilgamesh. That made me want to watch Darmok again. And two, there’s something I almost wrote last time, but didn’t quite make it there.

I know many people hate this episode. I know they say the premise is ridiculous. But here is where I think the critics are missing something crucial.

Ready?

We are the Children of Tama. We understand the world through metaphor. This is precisely what Piaget says about how we learn. We build on our prior knowledge and experience to come up with new understanding.

When a child learns the concept of “dog”, a new structure is built in her brain. When, next, the child sees a cat, she may say “dog”, trying to make a connection to what she already knows. A cat is a dog. Metaphor! Later, the child expands her understanding to see that cat is a new category, something like dog, but different, as well. Metaphors are beautiful because of course they are only almost true.

This will sound crazy, but what if the aliens depicted in this episode actually don’t communicate through metaphor? What if it’s us? What if our brains are so different from theirs that the universal translator simply gives us everything in a form it thinks we might understand? Everything for us is so tied to metaphor – “The Tamarians are aliens, the metal contraption they ride in is a spaceship, the person in charge is their captain.” All of these are models we build in our minds to help us understand a never-before-experienced situation. Also, all are metaphors.

I mentioned the last time I wrote about Darmok my favorite scene, in which the Tamarian captain Dathon pidgins his own language to help Picard understand, and to communicate back to him. Now I have a close second. Near the end, as the new Tamarian captain receives Dathon’s log from Picard, he says “Picard and Dathon at El-Adril”.

He’s just created a new metaphor! We’ve just witnessed the language grow. Note that this metaphor does not have the same meaning as “Darmok and Jilad at Tenagra.” Dathon died. This story has a new meaning – sacrifice for a noble cause.

So that blows my theory about we being the Children of Tama, right? No. Who is watching the show? Not the Tamarians. We are. Why? For the same reason we watch any program, or read any book, or listen to any song. Stories change us. We grow by adding metaphors. Over the course of this extraordinary episode, Dathon and Picard have taught us something: about life; about communication; about understanding, about sacrifice. Picard and Dathon at El-Adril. And we will never be the same.

Solomon Northrup, a free black man living in Saratoga, NY with his wife and two children, wakes up one morning in 1841 to find himself in chains, locked in a dank cellar. A man beats him bloody until Solomon renounces his freedom. For the next 134 tense minutes, we follow Solomon’s journey through the cotton and sugarcane plantations of Louisiana, witnessing the horrors that arise when human beings are property.

I found myself at the edge of my seat, unable to even look away from the screen. Rarely has a movie affected me so deeply. I was reminded forcefully of a television adaptation of The Diary of Anne Frank I saw as a young boy. In both cases I was struck at the injustice of having your life ripped away, of having no recourse, no chance of escape.

One of the striking features of the movie was the beauty of the landscape. Bucolic fields, warm, sunny days, lovely mornings, grand mansions, hoop skirts and horses. But just under the surface of all that beauty were the whip, the noose, the rapist, the torturer, the injustice, the illogic, the unfathomable despair. This is a movie that grabs you and will not let go.

Afterwards I read reviews and comments. At first I felt anger, incredulity, and deep sadness at the defensiveness and knee-jerk claims of reverse racism. I’m over it now. The whole point of a free society, after all, is that everyone has a voice. People are different, and those differences will naturally be reflected in our reactions to art. If we really believe in freedom, we have to believe that all reactions to such things must be legitimate. Even the really dumb ones.

OK, I’m a middle aged white guy, not Jewish, not black, not any minority class to speak of unless you count atheist. And I don’t. Could I understand this movie? Of course I could. That’s the point of art. It changes you. We all build understanding in our own way; we follow our own path. Some paths lead nowhere – that’s the danger and the joy of freedom. Other paths lead to a deeper, better (but still imperfect) place. You can’t know until you take the journey – for the journey itself is how you know.

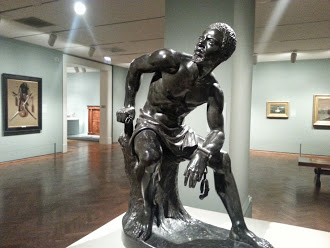

When my family and I went to Chicago a couple of months ago, I was struck by a sculpture at the Chicago Art Institute. I took a picture, then forgot about it until just now, as I was thinking about 12 Years a Slave. Here’s the sculpture.

It’s called The Freedman by John Quincy Adams Ward. What you have to understand about The Freedman is that you are first drawn to the face, the strong arms and shoulders, the chest. This is a person, beautiful and strong, an actor in the universe. He could be Achilles, or David, or Galileo. Then, and only then, your eye is drawn down to the left wrist to reveal the chain.

The thought that anyone ever had the right to own this person as property is immediately absurd. The evils of slavery emanate from this absurdity. The sculptor communicated this to me in a way I could understand, intensely and viscerally, like a wave washing over my entire being. Just as the makers of 12 Years a Slave communicated with me. These works of art moved me, shook me, helped me (no, forced me) to build new paths. What more could you want?

A recent discussion about young Earth creationism has got me thinking about my view of the world.

Young Earth creationism (YEC) is such an easy target that is is tempting to be misled, and I realize that I have often fallen into the trap I’ll shortly describe.

YEC proponents claim that the Earth and in fact all the universe is something like six to ten thousand years old, that humans and animals appeared in pretty much their modern form at the beginning of time, that most extinctions occurred and geological formations like the Grand Canyon appeared due to a single worldwide flood, and so on, and that God was responsible for it all. The first part of this argument is so bad that it’s easy to get stuck there, and never get to the second part of the argument, which is in fact infinitely worse. This is the trap.

We can demonstrate that the universe is much older than a few thousand years. We can show that humans and animals have evolved. We can present evidence for the slow formation of landforms. But these demonstrations have no effect on YECs. Why? Because that’s not what YEC is truly all about. Instead, and this is the key point we miss, YEC is actually all about the second statement “God did it.” That’s a statement we can’t refute – which ironically is precisely what makes it such a spectacularly bad explanation.

Old-Earth creationists, intelligent designers, and so on, are far more clever than YECs, and we can see in their arguments the crux (no pun intended) of the issue. They might say, “Fine, we accept all that science and history and geography demonstrate. The universe is 13 some billion years old and began with a Big Bang. But God still did it.” Even though this argument matches (by definition) all the findings of science, it is still a bad explanation.

Let’s set up an imaginary scenario in which YEC or some other similar claim is not such fish-in-a-barrel easy pickings in order to explore why. Suppose an upcoming mission to the Moon discovers, inscribed in the original Hebrew, a replica of the Ten Commandments.

You can imagine the mixture of celebration, consternation, “I-told-you-so” finger wagging, and so on that would ensue. Would this discovery prove the existence of the supernatural entity called God?

Many would be convinced. If I’m honest to my convictions, I have to say that such a discovery would not, in fact could not, convince me. For even with evidence like this, the idea that “God did it” is still a spectacularly bad explanation. If I accept the idea that life (not just science) is all about finding good explanations, then even with the inscribed tablets from the Moon I would have to reject the “God did it” argument as a bad explanation.

What would I say instead? First eliminate the obvious. Is it a hoax? Is this a modern Shroud of Turin, created by Earthlings with an agenda? If we can eliminate that by, perhaps, obtaining an accurate date, demonstrating that this material originated on the Moon itself, showing that the letters were carved in a way inconsistent with a hoax, and so on, then we move on.

Could it be that the tablets arose via natural processes? This is an exceedingly bad explanation. However, it is still better than the idea that a supernatural entity acted in our universe, for the simple reason that the tablets themselves must contain far less unexplained order than the entity that supposedly carved them. Even so, I’d be quite unsatisfied with such an explanation.

No, my conclusion, I believe, would be something like this: the stories of the Old Testament have more truth than I’d supposed. Perhaps there were original tablets, maybe even a person named Moses who received them, and perhaps he even thought he’d received them from God. But such a God, acting in our universe, must be part of our universe, must be, perhaps, a creature like the “Q” of Star Trek, an immensely powerful, knowledgeable, yet still evolved being of our universe, a being that still obeyed and obeys the laws of physics.While we have no evidence for such a race (other than these imaginary tablets, of course), this is still a far better explanation than the supernatural notion that “God did it.” Faced with magic, we must try to discover how the magic works.

What was the point of this imaginary exercise? Just this: the fact that YEC is demonstrably wrong is beside the point. Even if, through some utterly unlikely chain of events, modern science were to discover that the YECs were right all along, that the Earth really is only a few thousand years old and so on, such a discovery in no way validates the much worse claim that a supernatural entity known as God is responsible for our existence. Supernatural explanations are always bad explanations. This is why “debating” YECs (or old Earth creationists, or intelligent design advocates) is pointless.

This argument might feel uncomfortable. It seems like dogma, this out-of-hand denial of the supernatural. Isn’t this the equivalent of a religious claim, an unproved (and unprovable) belief that the universe makes sense? Consider the alternative (which is very much the “world” we live in, and by world I mean society). She claims “God did it”. He claims “The Flying Spaghetti Monster did it”. Another claims Allah, Vishnu, the Raven, the Great Turtle, and so on. Supernatural claims are infinitely variable because they are definitionally untestable. The only path forward we’ve ever found, the only way we’ve ever made any progress, is by assuming that the world makes sense.

Arthur Clarke famously said “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Bull, I say! If you believe in reason, you will analyze the “magic”, find out how it works, and change your view of the world to accommodate the new information. But you won’t give up on reason. If we decide that “magic” is both real and unexplainable, we’ve lost.

And so we enter upon the third day of the chase for Moby Dick. We know how it must end. I trust I won’t be spoiling it for anyone to cover the events that finally doom both Ahab and his ship.

I have to say that, compared to Ahab’s thrilling soliloquy in the storm, the writing of this final chapter left me cold. It was old, worn, tired, just a playing out of what had to happen to cap this epic tale with a suitable Shakespearean finale. I was disappointed.

First Ahab, following Macbeth, begins the chase by stating once again his belief in his own immortality.

“Drive, drive in your nails, oh ye waves! to their uttermost heads drive them in! ye but strike a thing without a lid; and no coffin and no hearse can be mine:- and hemp only can kill me! Ha! ha!” (p 834)

You know what’s coming next, don’t you? Moby Dick arrives on the scene, causes his usual havoc with every boat but Ahab’s, and then reveals a human figure pinioned to his back. It is, of course, Fadallah, “his sable raiment frayed to shreds; his distended eyes turned full upon Ahab.” (p 835)

Fadallah has gone before Ahab, and Moby Dick himself is the first hearse – remember, “the first not made by mortal hands.” Clever, Melville, very clever. Ugh.

But still following the path first trodden by the Scottish king, Ahab holds onto his belief that the full prophesy cannot possibly come true. “Where is the second hearse?” (p 836) Ahab shouts to the sea. It’s a little like the guy who says, “Let’s split up,” after they discover the dismembered teenager in the slasher movie.

And of course you know what’s coming now. Ahab once again harpoons Moby Dick, and the whale snaps the line. Then, in an act that would be implausible were it not the replay of an actual historical event, Moby Dick aims headlong not at Ahab, but at the Pequod itself. When the great whale collides with the great ship, the wound Moby Dick makes in her hull dooms the Pequod to sudden and irrevocable collapse. In short order, the ship goes down. It is, of course, the completion of the prophesy.

“The ship! The hearse! – the second hearse!” cried Ahab from the boat; “its wood could only be American!”

Oh, please. Oh, barf. Why is it that every prophesy ever made has to come true, but only in some twisted and unforeseen way? And why must every “hero” misinterpret the prophesy, leading to his downfall? Can’t anyone think of anything else?

Once again like Macbeth, who gets to shout “I will not yield” before his inevitable end, Ahab still has his famous final attack upon Moby Dick.

Towards thee I roll, thou all-destroying but unconquering whale; to the last I grapple with thee; from hell’s heart I stab at thee; for hate’s sake I spit my last breath at thee. Sink all coffins and all hearses to one common pool! And since neither can be mine let me then tow to pieces, while still chasing thee, though tied to thee, thou damned whale! Thus, I give up the spear!”

And somehow, as this harpoon goes flying toward Moby Dick, the hemp rope (Get it? Remember the prophesy? Remember the gallows?) catches Ahab around the neck and pulls him right out of the boat. His harpoon once again embedded in Moby Dick’s flesh, Ahab and the whale together disappear under the waves and out of our story. The Pequod sinks (not without one more grotesquely symbolic drowning – I’ll let you read that one yourself, it’s so ridiculous I can’t bear to write of it). Next a coffin-turned-lifebouy explodes from the water, and Ishmael (remember him? The narrator? The star of the book’s first twenty chapters?) grabs hold. A passing ship rescues him, the lone survivor of the tragedy, and our sad story finally ends.

But wait. What of the whale? As stated before, where Starbuck sees Ahab’s desire for vengeance as blasphemous, we moderns see it simply as misguided. We know that whales are animals, not evil spirits. We know that if you try to kill an animal, you should expect it to fight back. I think it’s clear that Melville agrees with Starbuck, as the very air and water rebel against Ahab, sending sharks to chew on his boat’s oars, eagles to steal his ship’s flags, and lightning storms to reverse the Pequod’s compasses. We look at Ahab and see error. Melville looked at Ahab and saw sin.

So is there nothing to redeem this failure of human spirit? After 845 pages, does Melville leave me nothing but a morality lesson about flying too close to the Sun? Maybe not. But the hope I take from the story comes from a remarkable place.

Speaking of remarkable, it is worth stating that, for all the talk of Moby Dick, the whale itself does not even appear in the book, except in the tales of others, until chapter 133. And when it finally does appear, it doesn’t resemble at all the monster that was described in ridiculous and overblown prose in chapter 41.

(S)uch seemed the White Whale’s infernal afore-thought of ferocity, that every dismembering or death that he caused, was not wholly regarded as having been inflicted by an unintelligent agent. (p 266)

Yet when finally the whale is seen up-close by the sailors of the Pequod, here is the description Melville gives us: “A gentle joyousness- a mighty mildness of repose in swiftness, invested the gliding whale.” (p 807) Is this the unconquerable beast that thirsts for human blood? But wait, maybe the legendary ferocity will appear once the attack has begun. No. While crafty and experienced in avoiding the harpoon and knocking the whalers from their boats, in each encounter Moby Dick swam away while helpless men floated in the ocean like little crunchy snacks.

Melville describes Moby Dick as an animal merely trying to survive. This is made clear by Starbuck’s shouted words to Ahab just before the final battle on the third day of the chase.

Moby Dick was now again steadily swimming forward; and had almost passed the ship, which thus far had been sailing in the contrary direction to him, though for the present her headway had been stopped. He seemed swimming with his utmost velocity, and now only intent upon pursuing his own straight path in the sea.

“Oh! Ahab,” cried Starbuck, “not too late is it, even now, the third day, to desist. See! Moby Dick seeks thee not. It is thou, thou, that madly seekest him!” (p 836)

And so it goes until Moby Dick defies all convention and rams the Pequod itself. As mentioned before, this is so unlikely that it would have been quite implausible had not a similar event occurred in the year 1820, when the whale ship Essex was sunk by a collision with a sperm whale, apparently driven mad by the hunt.

We know today what Melville could not. The oil-filled head of the sperm whale that made the creature such a valued target for whalers is not a floatation device or a battering ram, but rather is a finely-tuned instrument for focusing sonar signals through dark ocean depths. It seems incredible that any sperm whale, no matter how provoked, would purposely ram this delicate organ into a ship. And yet we know it happened in reality at least once. So Melville’s collision was not wholly the creation of his own fancy. But again, perhaps, Melville misinterpreted what had really happened.

After Ahab’s last stand, both he and Moby Dick disappear from the story. We can be certain that Ahab perished in that final plunge (otherwise the prophesy would not be fulfilled, and we know that’s not allowed), but of the whale, we are left with nothing but silence. In the absence of evidence, then, we speculate.

Let us here, then, give Moby Dick a suitable finale. I imagine this magnificent whale, so tormented by its pursuers that, after three days of unrelenting pressure, Moby Dick finally chose to confront the creature that would not leave it be – the Pequod itself. In ramming its forehead into the Pequod the whale must have mortally damaged itself, but at least it would finally be free of the torment of this unceasing hunt. Stunned and injured, Moby Dick took one final insult from Ahab, catching Ahab’s last harpoon, then spiraled down into the abyss, carrying the vengeful madman down and down, creature and tormentor now linked forever.

In smashing its head into the Pequod, Moby Dick did what Ahab could not. Where Ahab followed prophesy, was “the fates’ lieutenant” and acted “under orders”, Moby Dick made a choice. And maybe it is in that final act of free will that we can find some reason for hope.

A Short Afterward

I’ve been a bit hard on Melville in these blog entries. I judge him with my own modern eyes, and that’s not really fair. But like Melville I bring my own time with me wherever I go. How could it be otherwise? I’m certain people of the future will look back at us with equally critical eyes. In fact, I hope they do. As David Deutsch said, “Only progress is sustainable.” (BoI, p 389)

I began this project with the goal of discovering how (if?) reading Moby-Dick had changed me. Did I succeed? Certainly, this reading changed my view of what had up to now been my favorite Shakespearean play, Macbeth. The book and the play have so many parallels toward their ends that I think I will never again consider one without the other. And I’m not sure that’s a good thing. I used to really like Macbeth.

On the brighter side, Moby-Dick left me fascinated about the history of whaling. I’m longing now to visit New Bedford and Nantucket, to stroll the streets once trodden by Ishmael, Queequeg, and even Ahab as they prepared to sail through the gates of the wonder world and into the wide ocean beyond. I did, I have to admit, enjoy the adventure.

But more deeply, Moby-Dick, and its consideration in light of The Beginning of Infinity, The Better Angels of Our Nature, and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, has reaffirmed in me my core belief in the power and the primacy of the individual. There is nothing better than being alive in this world, to know that, in Walt Whitman’s words, “the powerful play goes on, and you will contribute a verse.” What more could one ask for than the chance to play in this unscripted, unbounded drama? “All right then,” Huck said, “I’ll go to hell.” We are not guided by fate, we are not controlled by destiny. No invisible hand presses down upon us. If we feel such a hand, it is of our own making. We are not passive players in a tale that has already been told. Rather, we are the writers of our own story. The page, for now, is blank, awaiting the next verse. What will that verse be? We, and we alone, decide.

I finished The Fountainhead for a second time. I was spurred to read it by my disappointment at the Beginning of Infinity community. I sense in many of them the sort of libertarian over-indulgence I found in Ayn Rand in The Fountainhead. I wanted to go back and try to understand how and why Rand came off the rails, to see if perhaps I could sense the same failure in the real-life philosophy of the BoI community.

At one point in the book, Catherine shouts out, “I’m not afraid of you, Uncle Ellsworth!” It was tragic, because it was the last truly independent act Catherine would undertake. Hopefully my title won’t lead me to a similar fate.

I really do love parts of The Fountainhead. OK, the rape scene (really!) is an unnecessary vulgarity and a portent of the further vulgarities to come. But other than that, I really do admire Howard Roark’s sense of self-worth and self-satisfaction. Every humanist should read the section on Roark’s Stoddard Temple. This is a place I wish I could visit, and Howard Roark built it.

But now that I’ve read the book a second time, I see Rand’s mistake. The Howard Roark who build the Stoddard Temple never would have worked in secret on the Cortlandt project. The Howard Roark who built the Heller House and the Cord Building and the Enright House would have gone to the committee himself, stated his terms, then walked out when they refused him.

Why doesn’t the Howard Roark (now a much more established architect) of the second part of the book do just this? If he’s interested, he should say so, and say how he would do the work. Maybe (ok, probably) they’d refuse him. But their inability to accept Roark’s conditions are exactly what make Roark’s scheme with Peter Keating untenable. Roark’s experience (we assume the same experience that keeps him from going for Cortlandt in the first place) should have told him that his deal with Keating was doomed to failure.

When Roark saw Cortlandt perverted, he should not have been surprised. Roark’s character fell apart with his secret deal with Peter Keating, not with his illegal dynamiting of a building that wasn’t his. That was Ayn Rand’s mistake. Roark’s dynamiting of Cortlandt was not a necessary consequence of his philosophy. Instead, the whole Cortlandt episode was a failure of Howard Roark to live up to his own ideals.

So there, Ayn Rand. You don’t scare me anymore.

Now back to my regularly scheduled non-fiction.

The new book I just finished, The 4% Universe by Richard Panek, had a mind-blowing fact. This is the Hubble Deep Field image.

In 1995, for 10 days the Hubble Space Telescope focused on a single spot of sky. The spot was the size of a grain of sand held at arm’s length. In case you haven’t held any sand lately, that’s really, really small.

The 10 days of light collection resulted in an image. The image showed galaxies. Lots of galaxies. Around 3,000 galaxies, each with 100 billion stars, give or take a few billion. 3,000 galaxies in a grain of sand. That number staggers me.

But there’s more than that. There’s nothing unique about what Hubble did. That light isn’t limited to the HST. It is here. Now. Bathing the Earth, as it has for all the billions of years our planet has been here. Every time you look up at the sky, you are capturing pieces of light from more galaxies than you could ever count, 3,000 in every sand-grain-sized spot. All those photons are always there, day or night, raining down on us. Some of those pieces of light are 10 billion years old. That means they left a star (almost certainly now long-dead) billions of years before the Earth even formed. During that photon’s travels, the Earth coalesced, life evolved, intelligence arose, and you happened to turn your head to just the right spot to catch that photon in your eye, while billions of others landed instead on your head or in your eyebrow, or missed you entirely. All those galaxies, whispering to us across time and space, and most of them we will never hear, never see, never know.

But that picture above, a picture that none but our generation could ever have seen, gives us at least a little glimpse of just how unfathomably big this universe really is.

Incredible.

I’m taking a short break from the story of helium to revisit a previous topic that has nothing to do with science or sea turtles. But it gives me a different kind of wonder. And I feel the need to defend it.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is under attack again. There’s a new version coming out in which “the n-word” is replaced with “slave”. For those of you squeamish about such things, I warn you that I’ll be using “the n-word” later in this entry to talk about what I still believe is the most important work of fiction I’ve ever read. So bail out now if you must.

The most important moment in the book is when Huck is struggling with himself over what to do about Jim’s imprisonment on the Phelps’ farm. Jim is a runaway slave. Huck has helped Jim to escape Miss Watson. In Huck’s world, that’s stealing. It’s taking someone else’s property. It’s not just a crime, but a deep sin. The culture Huck grew up in makes no qualms about it. If you behave in this way, you are damned. Helping Jim escape is stealing. Huck writes out a note to Miss Watson explaining what she must do to get Jim back. And then, staring at the note, he starts thinking.

It’s so important to remember that Huck knows exactly what society is telling him. We as modern readers of course side with Huck in his doubts. We don’t see people as property. We don’t see some people as less human than others. We see Huck’s act as heroic. But he didn’t see it that way, and that’s what is important. Nothing in Huck’s world, nothing, except his own experiences with Jim on the raft, could have given him any idea that Jim is a human being. It’s only after Huck gets to know Jim, is cared for by Jim, comes to love Jim, that he can see Jim as a human being. And Huck, the great hero that he is about to become, finds truth not in the society around him but instead in himself. He tears up the note and speaks those wonderful, freeing, self-affirming words, “All right then, I’ll go to Hell!”

The use of “the n-word” both before and after that scene is the great controversy. Many would argue that this is just the way people spoke back then, and so of course Twain was just trying to reflect reality. Don’t gloss over reality for political correctness. Fine, all well and good. But for me it goes so much deeper than that. The use of the word in one particular scene shows exactly what the word meant, what it maybe still means for some, and just how far Huck had come – a distance we all can only hope for in so many areas of our lives.

After Huck made his decision, he went to the Phelps’ farm to try to free Jim. In talking with Mrs. Phelps, Huck spins a lie about a steamboat trip to throw the woman off his track. Here it comes.

“It warn’t the grounding — that didn’t keep us back but a little. We blowed out a cylinder-head.”

“Good gracious! anybody hurt?”

“No’m. Killed a nigger.”

“Well, it’s lucky; because sometimes people do get hurt. “

And there it is. That is why you simply cannot edit Huck Finn. Mrs. Phelps (Aunt Sally, as it turns out) asks if anyone was hurt when the steamboat cylinder exploded. Huck, knowing exactly what Aunt Sally would expect an ordinary boy in her culture to say, exactly what a slave-thief wouldn’t say, tells this good, sweet lady that no one was hurt, but the explosion killed a nigger. And Aunt Sally responds accordingly, that it was lucky that no person was hurt.

If you change that word, you lose the sting, the blow, the utter irony of the scene. Huck gets it. He gets that Jim is a man, a human being, someone who deserves love and respect – and freedom. Aunt Sally will never get it. Jim is just a nigger, not a person at all. It has nothing to do with his slave status. It is Jim’s humanity that is in question – who he is, not what he does. And Huck knows exactly where Aunt Sally is, exactly what Huck must to do to gain her trust. But, bless him for being the hero he is, Huck has already decided he won’t be the person Aunt Sally and the world want him to be. “Alright, then, I’ll go to hell!”

Don’t change a word of Huck Finn. Instead, learn from what’s there. Huck made the journey that is almost impossible to make. He looked into himself and found truth.

OK, back to helium.

I’m not often a fan of fiction. I recently finished Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials trilogy and had a mixed reaction. But I find a lot to like in Pullman’s underlying philosophy. And the more I read of others’ negative reactions to the trilogy, the more I find myself drawn to its central message. Organized religion finds lots not to like about Pullman’s books, and they’re absolutely right. They should be threatened by these books, because they strike right at the heart of everything that’s wrong with much of religious philosophy.

I became very interested in Pullman’s vivid description of what it is like to have one’s daemon “severed”, and in reading more about it I came across this blog.

What I’m about to write is totally unfair; the author of this blog is probably a fine person, a deep thinker, a good parent, and all the rest. But his words about Pullman’s book repulse me in (I suspect) a way exactly opposite the blog author’s intent. Here’s what he wrote:

“In a sense we are all severed children, cut off from God. The Incarnation has made it possible for us to begin to re-establish the connection. The choice is there, for everyone and for all time. The mere knowledge that this is possible, and the faith to embark on the process, is enough to undo many of the effects of the severing; it accounts for the serenity which is one of the things we always sense in someone who seems to be far advanced along the path.

“The truly severed, those who most resemble Pullman’s severed children—lost, empty, half-dead creatures—are those who deny the very possibility of what they need to be whole. Or, in other words, those who believe what Pullman preaches. Because it is a necessity for us to accept the reality of the spirit in order to be whole human beings, Pullman and his fellow atheists are like miners trapped in a cave-in, breathing stale air which will soon be exhausted of oxygen, and in delirium denying that there is or could be such a thing as fresh and wholesome air.”

Speaking as a lost, empty, half-dead creature (who is right now looking at a beautiful blue sky and wondering how anything can be so perfect), all I can say to the author is, “Can you hear yourself? Can you hear the arrogance and presumption?” But that’s not really what I want to write about. What I want to write about is the twisting of concepts that I’ve found in my own limited experience to be so representative of all that religion tries to do.

In His Dark Materials, the idea of the daemon is you. Not some otherworldly spirit, not some generous gift from somewhere else. It is you. Your hopes, dreams, fears, loves, aspirations, the thing that makes you yourself and not someone else. The loss of your daemon is the loss of your identity.

And this is what religion asks.

Religion (my religion, anyway, the religion I grew up with) tells us that what’s good is actually bad. If you love your child more than God, you’re a sinner. God might test you by ordering you to kill that child. Abraham loved God more than Isaac, and was duly rewarded. I (and you, too, and every good and decent person I know, I suspect) would have failed that test, and been punished by God.

Religion tells us that knowledge is bad. Eve chose knowledge, instead of eternal infancy and ignorance, and she and Adam were punished by God. Read Genesis 3:22. God didn’t want their eyes opened. God wanted to keep them ignorant forever.

Religion tells us that doubt is bad. Thomas demanded proof that Jesus had risen from the dead. Jesus gave him proof, then chided him, praising those who believed without proof.

Religion tells us to submit, to give ourselves to God, to abandon worldly things. The world is sinful, no good, impure. Turn your back on it, and you’ll be rewarded. Later.

Look carefully at this list. Don’t love anything, even your own children, more than God. Don’t seek knowledge. Don’t doubt. Don’t enjoy life.

In other words, be severed.

In His Dark Materials the Church decided to try severing children to save them from Original Sin. In our world, religion does the same thing, metaphorically. Then (and here’s the really clever trick) religion tries to give you this false daemon they call God.

Read carefully the quote above. Notice how the concept of the daemon is so cleverly turned upside-down. You start off severed. Only faith in God can make you whole again. Anyone who tells you different is just, what was it? Oh, yes, “like miners trapped in a cave-in, breathing stale air which will soon be exhausted of oxygen, and in delirium denying that there is or could be such a thing as fresh and wholesome air.”

I deny no such thing. I say the air is fresh and wholesome. Where the author sees a cave-in, I see life: messy, imperfect, beautiful life. We start off whole, we humans. We start off with brains and eyes and ears to take in all that is around us, starstuff contemplating the stars. We start off (hopefully) with parents and community who give us the tools the learn, the freedom to make mistakes, and the support to recover from those mistakes. We start off with choices. Think of the power in that! Is there any greater freedom than the freedom to choose?

Some choose a religious path, or an artistic path. I have chosen a path that helps me see the beauty and wonder of the natural world. All these paths are perfectly valid in their own way, of course. The tragedy I see is in denying the choice itself. Don’t let others choose your path. Don’t let them use fear, intimidation, and empty promises of something better around the corner to fool you into not trusting yourself. Joseph Campbell used to say “follow your bliss.” He could just as well have said, “follow your daemon.”

In our world we can’t see our daemons. But they’re there. We all have them, and we know them well. They’re the voice you hear as you stand in the shower, contemplating your day. They’re the joy you feel on a beautiful blue-sky day. They’re the tears that well up at the end of a Hallmark commercial. They’re the whisper in your head when you hear a ridiculous story, saying “come on!” You know your daemon. Your daemon is YOU!

Don’t let them sever your daemon. You have the power to choose. Use it.

I’ve read and reread the passages on quantum erasers and delayed choice in Brian Greene’s wonderful book The Fabric of the Cosmos. I think I’m finally getting a feel for what it means. And I also think the existence of quantum erasers says something amazing about, believe it or not, free will.

Stay with me here, because the going will be a bit treacherous. I’ve written before about the double slit experiment. I’ve also written a little bit about entanglement. When you combine those two crazy ideas together, you get, well, craziness. But a very particular kind of craziness, the kind that makes the whole mind-blowing subject, I think, a little more human.

OK start with the basic idea. You can’t know both the particle-nature of a photon (which slit it went through) and the wave-nature of that same photon (interference pattern). Anything you do that reveals “which path” information automatically makes the interference pattern disappear.

What’s interesting about the quantum eraser is that you can set up things so that which path information exists, but is still hidden. One way Greene describes this is by polarizing the photon either clockwise or counter-clockwise. If you do this, even if you don’t collect the information, the interference pattern is destroyed. This is key: the mere potential of collecting which path information destroys the interference pattern. This is important for later.

The quantum eraser takes that information back out. The polarization is erased by removing the tag. Now the photons can interfere once more. Remember, as long as the potential for which path information exists, the interference pattern disappears. But (and again, this is key) once that potential is erased, the interference pattern comes back. This is important, too.

OK, now let’s think about another way to make which path information potentially available. This is a method that is even less invasive than the polarized tag. This time, we use something called a down-converter. Where at first one photon existed, we now create two, each with half the frequency of the original photon, and each entangled with the other. Call one photon the signal photon, the other the idler photon.

Suppose we send the signal photons toward a double slit. Will they form an interference pattern? The answer is, it depends on the idler photons. As long as these idler photons exist and give us the potential to discover which path information, the answer is no, no interference pattern will form. If, on the other hand, these idler photons are recombined in such a way that which path information becomes impossible to retrieve, then the interference pattern, in a certain specific sense, reappears.

Here’s the incredible part, though. The choice about what to do with the idler photons, whether to measure them directly or to recombine them to erase which path information, can happen after (even well after) the signal photons have formed their pattern. Note that, due to some clever bookkeeping by nature, you can never actually “see” the interference pattern until you obtain some extra information about the recombined idler photons. It’s all part of that amazing way that nature has of covering her tracks. It’s pretty clever, and if you want to know more about it I urge you to read Greene’s book, this Wikipedia article, or even the original paper (look at how graphs 3 and 4 each show an interference pattern, but when you combine them into graph 5, as always happens in the real experiment, the pattern disappears. Nature is shrewd!)

But astounding as all that is, it’s still not the most amazing piece of this. Here’s the most amazing piece. We already saw that we can reveal honest-to-goodness, no-mistaking-them interference patterns if we erase the which path information before the photons hit the screen. Remember the important points bolded above. What we can’t do is reveal an honest-to-goodness, no-mistaking-it interference pattern if the which path information is erased after the signal photons hit the screen. There’s a before-after dichotomy. The universe behaves differently regarding a choice that’s been made and a choice that might be made. And while it would be mind-blowing either way, I find this result (the future can’t affect events that have already happened) just as mind-blowing, maybe even more mind-blowing, than the alternative. Why? Because as long as the idler photons exist, as long as the potential for which-path information is there, the signal photons will not form an interference pattern. It’s as if they’re saying, “You might find out, you might not, so we’re not taking any chances.” But if we might find out and we might not, then we have the choice. We aren’t constrained by the past, and all future paths are open to us.

The refusal of those stubborn signal photons to form an interference pattern, no matter how we promise that no, really, we’d never go and detect your idler friends, demonstrates to me an amazing fact. We have free will. The future is open. We can make our own choices.

This is a big deal, because there are philosophies that say the future is just as determined as the past, that time is an illusion, that all future events are controlled by conditions right now. But the delayed choice quantum eraser denies that idea. It says that I control my own destiny, and the universe, recognizing my autonomy, must behave accordingly. And that’s pretty cool. Damned be determinacy! Long live the idler photons, for they have set us free!

For whatever reason, I’ve been thinking lately about the Abraham and Isaac story in Genesis. I don’t know why, but that story bothers me like none other. Part of it, I’m sure, is being a father, having the experience of watching a child grow from a newborn baby into an aware, sentient, thinking and feeling human being. Watching my children discover their world, and seeing it new again, through their eyes, has been the great joy of my life.

I’ve read all the apologists’ explanations of the Abraham story. I still find it deeply creepy. But I was having trouble expressing what troubled me so much.

Then I thought of Huck Finn.

I recently finished (for probably the 7th or 8th time) possibly my favorite book ever, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. And it struck me. The crucial scene in my favorite book is a near-exact recreation of the Abraham and Isaac tale. With one crucial difference. Huck makes the right decision.

Think about the similarities. God knows that Isaac won’t be harmed. It’s all just a test. But Abraham doesn’t know.

Jim won’t go back into slavery, no matter what, because Miss Watson freed him. But Huck doesn’t know.

Huck knows the “right” thing to do, what God and society tell him to do, is to turn Jim in.

Abraham knows the “right” thing to do, what God has told him to do, is to kill Isaac.

But Huck has changed during his trip down the Mississippi. He’s discovered something he never suspected. Jim is a man. Jim loves his family. Jim gets lonely. Jim even loves Huck, cares for him, looks out for him, like no one has ever done before – certainly not Huck’s own father. Does Huck love Jim? I don’t know, but certainly Huck has learned something that has shaken him. Jim is a man.

And what about Abraham? Hasn’t he watched Isaac grow, learn, discover the world? Hasn’t he had even a piece of the experience that I and billions of other parents have had? There’s little to go on in the text, but God does say “Take your son, your only son, Isaac, whom you love . . .” which I read as an admission (the only admission anywhere in the text) that this is going to be a hard thing for Abraham. Abraham loves Isaac. Huck may love Jim. But Abraham definitely loves Isaac.

Huck is faced with a choice. He has the letter, the letter he’s just written, which might seal Jim’s fate. He could send it, and save himself from damnation. Or he could decide to steal Jim back out of slavery. What comes next is the most beautiful statement of individual choice I know:

“It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a trembling, because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

“All right, then, I’ll go to hell”- and tore it up.

It was awful thoughts, and awful words, but they was said. And I let them stay said; and never thought no more about reforming.”

Abraham had a choice, too. Here is Isaac, the son he’s been told to sacrifice, the son he loves. It was a close place. But we never find out what, if anything Abraham was thinking. Instead, we learn only that Abraham reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son.

Now we know what happened in both cases. Jim was already free, though Huck didn’t find out until the world’s first frat boy, Tom Sawyer, let him in on the joke. Isaac was never in any danger, though Abraham didn’t find out until the knife was in his hand. And yet the choices make all the difference in the world to the readers.

Huck chose against what the world and God had told him was right, and instead chose to follow his own experience. Abraham chose against his own experience of raising a child, watching that child grow, and growing himself to love that child, and instead chose to follow what he’d been told. Huck knew his choice would be scorned, knew he’d be dispised and hated by everyone who encountered him. Everyone except Jim, of course.

Abraham was praised by God and the angel, and given great blessings and rewards. Everyone would praise his name – except, I have a sneaking suspicion, Isaac, who would forever know where he really stood with the old man.

Huck Finn, surely everyone would agree, is a hero for his act of courage. If you doubt me, consider this. What if Huck had mailed the letter? Miss Watson was dead, Jim was already free. EXACTLY the same result would have occurred. But if Huck had mailed the letter, would he have been a hero for following the dictates of God and society? Of course not. His act of heroism was in trusting his experience. Jim was a man.

Huck is a hero precisely because he turned his back on God and trusted himself. Huck took the hero’s path. Abraham simply obeyed. Huck is a hero. What, then, I ask you, is Abraham?